Peat bogs

Peat accumulates in shallow basins with a minimum depth of 30 to 40 cm known as peat bogs (Fig. 1). Peat, also known as turf, is a dark mixture of minerals and dead or partially decomposed plant remains. The ratio between these two components can be quite variable. However, the amount of organic matter is usually higher than the one existing in most soils.

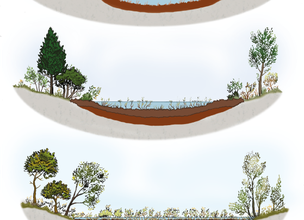

Peat bogs originate in places where the water flows slowly or accumulates and where a diversity of characteristic plants, such as some species of mosses, reeds and shrubs exist (esq. A). In an acidic and anaerobic (poor in oxygen) environment, these plants do not decay completely, and their remains mix with minerals resulting from rock weathering originating the turf. As turf piles up, it retains water thus generating increasingly moisty conditions. In developing peat bogs, turf accumulates at a rate of about one millimetre per year.

Most peat bogs existing in mid to high latitude zones of the northern hemisphere were formed in the final stages of the last glaciation, about 11.700 years ago. After, as the Earth became warmer, peat bogs rather formed at higher altitudes.

The turf in a peat bog is an almost continuous record of sediments, plants, pollens, spores, animals, and even archaeological remains laid up in place or transported from surrounding areas, especially by the wind. It is an ‘archive’ in which the preservation of these elements enables the reconstruct the history of the local ecosystem. This ‘archive’ also provides valuable information about environmental conditions and changes in the last 10.000 years (Holocene).

Peat bogs are one of the biggest reservoirs of carbon (C) on Earth. Vegetable organic matter is largely made up of carbon that is taken from atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) by plants during photosynthesis. When plants die, their remains become ‘imprisoned’ in turf under moisty anaerobic conditions that prevent their complete decay and ensuing release of carbon. Once ‘captured’ in turf, carbon may be held for millennia.

Peat bogs may also influence microclimatic regulation because they promote the formation of dew, frost and haze. On the other side, there is a significant flow of CO2, methane (CH4), hydrogen sulphite (H2S), and nitrogen oxide (N2O) between the turf and the atmosphere.

Turf is an important energy resource; it is used as domestic fuel in several parts of the world. Such as other fossil fuels, turf is a non-renewable energy resource: its extraction rate largely surpasses the slow rate of turf accumulation, about 1 mm per year.

Chãs de Arga peat bogs occupy an area of 591 hectares in the same place where Âncora river is born (Fig. 2). These peat bogs are part of the so-called ‘Atlantic peat bogs of the mountains of the Iberian Northwest’. The most ancient might have been formed 10.000 years ago but many of them are much younger, 2000 to 3000 years old.

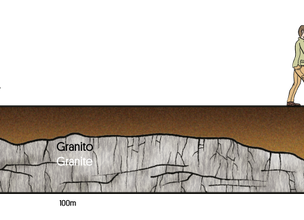

The interpretation of the GPR profiles carried out in Arga Grande peat bog allowed to understand its stratigraphy with some accuracy (esq. B).

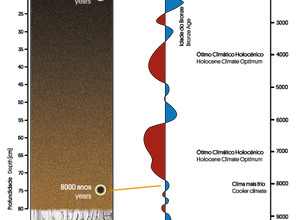

Mineral dating and the analysis of pollens preserved in the Chã Grande peat bog provided information on climate evolution of Northwest Iberia for most part of the Holocene, the geological epoch in which we are living during the last 11.700 years (esq. C).

In the beginning of the Holocene, climate was colder and herbaceous vegetation prevailed. Trees and shrubs existed only in protected places but as temperature rose, they began to expand, particularly Quercus robur. Shrubs developed mostly in higher places. During the Medium Bronze Age, shrubs diversified due to the escalation of agriculture and grazing with Quercus robur diminishing and Asphodelus augmenting.

In the last 500 years, a series of changes in the landscape took place due to the growing presence of man. In the 17th century, species like Quercus robur and Corylus avellane diminished; at the same time, 87 the number of heather and grass increased. This circumstance might be related to the massive exploitation of the local forest arising from the development of shipyards in Caminha and Viana do Castelo coastal areas. In the final years of the 17th century and during the 18th, pine trees developed as a consequence of the expansion of forest plantations. In more recent times, there is a decrease in pine trees and a marked increase in eucalyptus and grass.

Peat accumulates in shallow basins with a minimum depth of 30 to 40 cm known as peat bogs (Fig. 1). Peat, also known as turf, is a dark mixture of minerals and dead or partially decomposed plant remains. The ratio between these two components can be quite variable. However, the amount of organic matter is usually higher than the one existing in most soils.

Peat bogs originate in places where the water flows slowly or accumulates and where a diversity of characteristic plants, such as some species of mosses, reeds and shrubs exist (esq. A). In an acidic and anaerobic (poor in oxygen) environment, these plants do not decay completely, and their remains mix with minerals resulting from rock weathering originating the turf. As turf piles up, it retains water thus generating increasingly moisty conditions. In developing peat bogs, turf accumulates at a rate of about one millimetre per year.

Most peat bogs existing in mid to high latitude zones of the northern hemisphere were formed in the final stages of the last glaciation, about 11.700 years ago. After, as the Earth became warmer, peat bogs rather formed at higher altitudes.

The turf in a peat bog is an almost continuous record of sediments, plants, pollens, spores, animals, and even archaeological remains laid up in place or transported from surrounding areas, especially by the wind. It is an ‘archive’ in which the preservation of these elements enables the reconstruct the history of the local ecosystem. This ‘archive’ also provides valuable information about environmental conditions and changes in the last 10.000 years (Holocene).

Peat bogs are one of the biggest reservoirs of carbon (C) on Earth. Vegetable organic matter is largely made up of carbon that is taken from atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) by plants during photosynthesis. When plants die, their remains become ‘imprisoned’ in turf under moisty anaerobic conditions that prevent their complete decay and ensuing release of carbon. Once ‘captured’ in turf, carbon may be held for millennia.

Peat bogs may also influence microclimatic regulation because they promote the formation of dew, frost and haze. On the other side, there is a significant flow of CO2, methane (CH4), hydrogen sulphite (H2S), and nitrogen oxide (N2O) between the turf and the atmosphere.

Turf is an important energy resource; it is used as domestic fuel in several parts of the world. Such as other fossil fuels, turf is a non-renewable energy resource: its extraction rate largely surpasses the slow rate of turf accumulation, about 1 mm per year.

Chãs de Arga peat bogs occupy an area of 591 hectares in the same place where Âncora river is born (Fig. 2). These peat bogs are part of the so-called ‘Atlantic peat bogs of the mountains of the Iberian Northwest’. The most ancient might have been formed 10.000 years ago but many of them are much younger, 2000 to 3000 years old.

The interpretation of the GPR profiles carried out in Arga Grande peat bog allowed to understand its stratigraphy with some accuracy (esq. B).

Mineral dating and the analysis of pollens preserved in the Chã Grande peat bog provided information on climate evolution of Northwest Iberia for most part of the Holocene, the geological epoch in which we are living during the last 11.700 years (esq. C).

In the beginning of the Holocene, climate was colder and herbaceous vegetation prevailed. Trees and shrubs existed only in protected places but as temperature rose, they began to expand, particularly Quercus robur. Shrubs developed mostly in higher places. During the Medium Bronze Age, shrubs diversified due to the escalation of agriculture and grazing with Quercus robur diminishing and Asphodelus augmenting.

In the last 500 years, a series of changes in the landscape took place due to the growing presence of man. In the 17th century, species like Quercus robur and Corylus avellane diminished; at the same time, 87 the number of heather and grass increased. This circumstance might be related to the massive exploitation of the local forest arising from the development of shipyards in Caminha and Viana do Castelo coastal areas. In the final years of the 17th century and during the 18th, pine trees developed as a consequence of the expansion of forest plantations. In more recent times, there is a decrease in pine trees and a marked increase in eucalyptus and grass.

Esq. A - Development of a peat bog.

Esq. B - The geophysical survey with Ground Penetrating Radar done in the central area of Arga Grande peat bog identified the base of the peat bog at an average depth of 1.2 m, ranging from a minimum of 40 cm at the edges to a maximum of 180 cm at about 170 m from the beginning of the profile.

Esq. C - Approximate relationship between the stratigraphy of Chã Grande peat bog profile and the variation in average temperatures in the northern hemisphere over the last 11.000 years, based on dating and pollen content.

Location

Sra. do Minho, Montaria

Coordinates

Lat: 41.7979396

Long: -8.6908504

Hello little one!

I'm Piquinhos and I can help you learn more about the Geopark!

Technical details

Esq. A - Development of a peat bog.

Esq. B - The geophysical survey with Ground Penetrating Radar done in the central area of Arga Grande peat bog identified the base of the peat bog at an average depth of 1.2 m, ranging from a minimum of 40 cm at the edges to a maximum of 180 cm at about 170 m from the beginning of the profile.

Esq. C - Approximate relationship between the stratigraphy of Chã Grande peat bog profile and the variation in average temperatures in the northern hemisphere over the last 11.000 years, based on dating and pollen content.

Child Mode

Discover the geopark in a simpler format, aimed at the little ones.

Clique ENTER para pesquisar ou ESC para sair